Communicating with Bankers for their part in a CAP Financial Guarantee

A guide to discussing In3’s CAP funding program with bankers for either a Bank Guarantee / Standby Letter of Credit or Bank-endorsed Promissory Note

Most bankers — especially those involved with trade finance, retail banking, or traditional project finance — will not understand CAP funding at first, and will be confused about their part in providing a “Completion Assurance” guarantee of the type we can accept for project funding. They’ll be even more thrown off if you ask them about providing an “Aval” (a stamp or seal of endorsement) on our 1-page Promissory Note (more), an alternative instrument used by some developers. Why? A few possible reasons:

- Perhaps because the CAP funding structure and instrumentation is different and possibly new to them, but in some ways quite similar to what they already know well (such as commodity Documentary Letters of Credit, DLCs, widely used for import/export transactions).

- The sharp differences to what’s familiar is largely unexpected. Some bankers will ask “How come I do not know about this already?” and will be naturally a bit skeptical about any funding program involving elements that are new to them (which is, in turn, because CAP funding itself is fairly new to capital markets generally).

- They do not want to make a mistake, and due caution must be observed as they seek KYC and other standard practices to make sure the proposed transaction is efficacious and that their customer is being treated with due respect.

Let’s examine these assertions more closely. First, how do we know it will be entirely new to so many? Simple. Look at the numbers. There are at least 9,000 licensed banks globally (the number of SWIFT member banks), each employing a good diverse swath of bankers in an industry going through major changes anyway (2023 outlook from Deloitte). There’s a lot to take in. Fact is, our private family office partners innovated this approach to mid-market project finance; it uses structural and procedural solutions to several notorious problems, and seems unique in the capital marketplace. Because of this, most bankers will not have heard of CAP before.

How is it different, exactly? One key difference is that CAP funding uses standard bank instruments but in a non-standard way. CAP uses standard Demand Guarantee tools — either a Standby Letter of Credit (but not the aforementioned Documentary LC) with customary Brussels SWIFT or a bank-endorsed Promissory Note — per well-established International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) rules, such as URDG 758.

The distinction between types of instruments can be subtle, and hard to explain to bankers who are most familiar with Trade Finance tools, but also, due to instrument wording and business logic differences, quite an important determinant to what most bankers will initially say is or isn’t feasible, reasonable, and affordable. To be specific, trade finance transactions use LCs (or DLCs) to pay the seller once the buyer’s conditions are met. By contrast, instead of “cashing” or drawing on the DLC as the final step, with CAP funding’s Standby LC (SbLC) verbiage used as project completion assurance, once the project is completed and commissioned, the SbLC is allowed to expire on its maturity date with ZERO transfer of underlying cash value.

These are fundamentally opposite approaches, and with a lot of money involved, expect bankers to be extremely careful to get this exactly right without any guesswork. Best case will be to get some bankers to suspend judgement long enough to internalize the commercial context. So, to assist with forming a bridge (a meeting of the minds), you’ll need to explain this properly: upon reaching the project’s commercial operation date (COD), the BG/SbLC or Bank-endorsed Promissory Note (more on PNs) is allowed to reach its maturity date and is released along with any underlying collateral or asset value. No ongoing guarantees are required from the funder’s side COD onward, which is also how this type of guarantee is unlike a traditional loan guarantee, where the latter usually stays in place for the life of the loan.

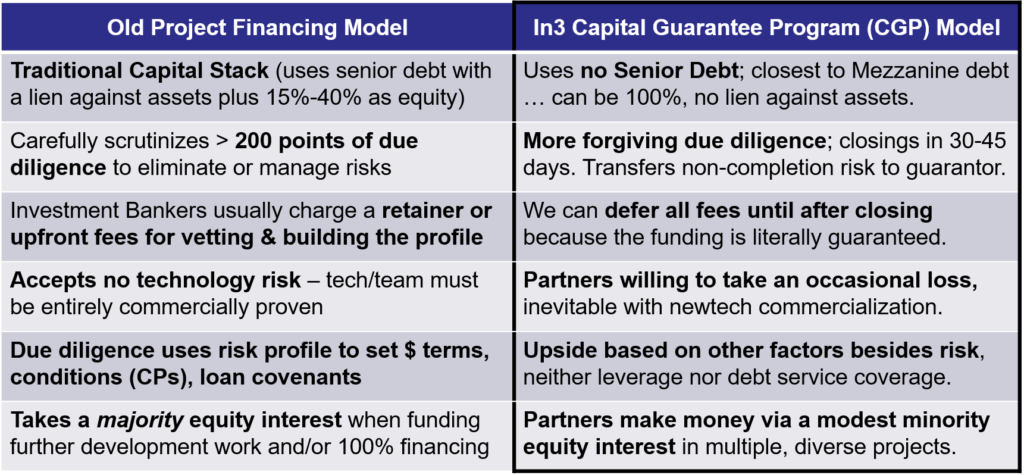

In3’s capital partners accept certain risks that traditional project financiers (like banks) definitely would not, such as whether or not there will be sufficient coverage for debt service, the ratio that shows the borrower’s ability to repay the loan, or even debt-to-equity (D/E), or Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratios, which are just not relevant to CAP funding’s structure (see glossary for definitions). Four key non-technical differences with CAP funding are defined here.

The above details examine just one instance of how experienced bankers can be thrown completely off, and history shows they will initially misquote the SbLC or AvPN cost (or even refuse to cooperate, stating quite emphatically that it cannot be done, and that nobody would touch it) if they are allowed to presume you are asking for a Documentary LC, if they sense a risk exposure, or if you are asking for a financial instrument in support of a funding program that makes no sense to them.

Many other basics remain in common between CAP funding and the traditional (fully bankable) project funding, so In3’s program can be confusingly similar to what they already know in that arena as well.

Another example: we’re using international “standby” or “demand guarantee” banking rules (International Chamber of Commerce pub. no. 758, 600 or 590), along with the Brussels SWIFT system, and prefer that guarantees follow verbiage that will seem quite familiar to bankers with experience in such undertakings. But that’s where the common ground ends and … like stepping into a foreign land, CAP funding redefines and improves upon many of the long-established traditions for financing mid-market projects, mostly because we ask clients to conduct a fast, up-front feasibility run-through, with no commitments to determine if the funding can be committed when the project developer and their bank do their part.

The guarantee itself serves as the essential backbone of an innovative structure that delivers an array of benefits to previously unsolved project finance challenges.

Is it better to discuss these differences from the start or to wait and see if the banker is going to track and deliver?

IT IS ESSENTIAL TO START OFF WITH THE CORRECT UNDERSTANDING, or not only will you be wasting your own time and theirs, but you will likely get frustrated that they’re not asking the right questions, not helping at all, and (at times) seem to be at odds with everything you say. Being polite enough not to say out loud “You are crazy and wrong!” many highly experienced bankers may be thinking it nonetheless.

It is common for there to be two different conversations happening without either party knowing it. Pay careful attention to their body language. Be aware of your own — especially if you start to feel frustrated. Developers tend to start by describing our program’s alternative methods while they’re listening through the lens of what is most familiar. It is major disconnect that must be headed off right away by asking pointed questions such as “Have you ever run into project finance from private sources that use completion assurance (financial guarantee) instruments?” Or better still “Who in your bank handles Private Wealth clients?” We’ve found that the Private Wealth managers at banks typically understand the reasons for these CAP funding innovations far better than the Trade Finance division ever will.

This communication is a fault-free zone. Keep your cool if your banker initially gives you “the look” (distain, disgust, frustration, or even “Why are you telling me this?”). There is also a natural defense mechanism to anything new in humans, and bankers are no exception. The unstated question “If this is real, why didn’t I know about it before?” will be part of their background thought process, so if you don’t explain the above points right away, or make sure you have approached a banker with a compatible experience base, you may find the rest of the conversation goes nowhere.

Some confusion is almost a certainty, at first, due to the flexibility of financial instruments generally, and that they are sometimes used fraudulently (scam artists are attracted to anything that involves millions of Dollars or Euros), plus the inherent complexity of such undertakings in financing projects of all types, so best to head off a potential misunderstanding at the pass, proactively, before it snowballs into a “stunning disconnect,” like two people describing the weather in two locations at a great distance from one another. There is no easy way to bridge across that divide without first agreeing on a roadmap so you can point to where you are now and where you want to go. See this technical roadmap (1-page PDF).

If you wait to explain these important differences until they already have formed the wrong impression (for example, the assumption that this funding uses a commodity Documentary Letter of Credit, used for trade-related import/export of goods), it will be much more difficult to get back on track. They may at first assume you are “out of your mind”, talking gibberish, or even somewhat threatening to their job (asking them to do something nonsensical) and might give you a look that says, “Why are you wasting my time with this nonsense?!”

This is surprisingly common at first? Why? Because this is likely new to them, and it seems so straightforward to just ask a banker to help. But here the better approach is to re-read the above, take your time, and do things properly. Anything else can ruin your chances with bankers that are prone to say “no” indirectly (perhaps by asking for higher fees, cash on deposit, or other unreasonable preconditions) simply because they are confused.

Bankers are as diverse as the day is long

That said, working with bankers from every continent and across diverse cultures and specialized work experience revealed some simple truths: no two bankers are alike, just as no two companies or people are. Even within a given bank and branch location, interpretations of the right format and presumed purpose of In3’s “completion assurance” guarantee tends to vary widely based on their prior experience, mixed with that particular banker’s personality and tolerance for novelty and risk.

The following observations are meant to help bring forward more of the common ground that leads to qualifying guarantees and fully funded projects at more favorable terms than could be otherwise obtained. We involve banks for the sake of project “completion surety” — not unlike insurance, but precisely different from insurance by type of coverage — our partner’s funding bank expects a financial guarantee that involves an issuing bank, not an insurance company or insurance product. Success tip for more on these differences.

How to Avoid Common Communication Pitfalls

The better practices avoid several common pitfalls — providing a way to head off miscommunication before it happens. As basic (and uncommon) as this “preemptive strike” may seem, it actually means you first listen and then verify your understanding (for more on how to do this see page 1 of this related guide). This extra step helps make sure your communication solves the issue at hand, and does not make matters worse.

Thus, we start by finding out what bankers already know and don’t know about this type of guarantee and its intended use. If they’re in Private Banking, they might understand it perfectly. If not, compare what they do understand (whatever is familiar) then draw out contrasts to illustrate how In3’s CAP funding approach, driven by our in-house Family Office partner, differs from traditional project finance structures and guarantee instruments.

Our goal here is to clarify the banker’s role/responsibility and set expectations up front for delivering the guarantee instrument. Bankers’ diverse experience gives rise to all sorts of disparate interpretations (often based on incomplete facts or erroneous assumptions) causing many to jump to conclusions that totally miss what we are asking them to do, why we are asking for this guarantee in the first place, and how it is a reasonably safe and mutually beneficial undertaking.

For example, once delivered, we cannot arbitrarily call the instrument, even in part, or make any claim against it. Only if there is fraud or provable malfeasance can such a claim be made, and even then, only after our funds have been drawn into the project’s (Special Purpose Vehicle) bank account us the instrument irrevocable. Even in this unlikely event of developer default, the burden of proof that there happened to be uncured breach of contract (fraud) is on us. This situation has never happened in our entire history, and really must not. It would be a strong negative reflection on all of us, especially so in the eyes of our bankers. Just explaining the mechanism often helps calm nerves, with more on that available at Frequently Asked Questions or via Myth #2, below.

Whether or not the bank is “exposed” in some fundamental way constitutes the most common concern. For bankers, this is mostly about the structure — inherent in the rules and agreements that govern the many possible uses of such financial instruments.

At In3, we have found the following explanations helpful — working to address the likely causes of communication disconnects. This is necessary because our program uses such an innovative structure that it will not make sense to well-experienced bankers at first. It requires a shift in their assumptions, and the more experience they have the harder it can be to make that necessary shift. It seems impossible or even a bit unnerving at first.

The second challenge, mentioned above, is that this approach to funding projects seems dangerously similar to more mainstream approaches, when in reality there are sharp and sometimes seemingly subtle differences that must be conveyed if we are to succeed. Fundamentally, the business model for project finance under CAP (formerly CGP) reflects a shift in the following assumptions:

Taking seriously the implications for banks and bankers means not merely offering an explanation of these differences, but actually conveying and verifying that the relevant facts are properly understood. Ask a lot of questions. To handle that back-and-forth dialogue means learning these distinctions yourself, or involving an In3 Affiliate, trained in how to assist project Developers with this all-important communication. (If you are good at self-study, read the rest of Guide to Gaining Guarantor Commitments for further how-to tips.)

In3’s Affiliates are also charged with making this shift in assumptions about who is responsible for this vitally important communication, aided by many tools, templates and articles, but in practice, the only thing that matters, and must drive our attention and actions, is when our client’s bankers verify their proper understanding of how this works.

In3’s Affiliates are also charged with making this shift in assumptions about who is responsible for this vitally important communication, aided by many tools, templates and articles, but in practice, the only thing that matters, and must drive our attention and actions, is when our client’s bankers verify their proper understanding of how this works.

Why is this communication with experienced bankers sometimes so challenging?

Our funding program is different enough (article highlights four key differences) that more trade-related experienced bankers are likely to miss the nuance. The more experience they have in the traditional pathways, the more likely that familiar approach will filter out the important differences. They won’t realize it, of course, but they will initially assume that any variations are just wrong or at best peculiar. As a result, unless we head off misunderstandings (the purpose of this article), bankers will tend to presume various untruths, and will often remain committed to those inaccurate perceptions until they receive strong evidence, if not actual proof, to the contrary. We are happy to report that such proof exists and can be provided at the right time, once we understand their exact concerns.

For reference, born of our own hard-won experience, here are the top 3 misunderstandings or “myths” about our funding program as often perceived by bankers, to help bridge some of the communication gaps.

1) Myth #1: This undertaking requires cash on deposit as collateral. Why would bankers assume this?

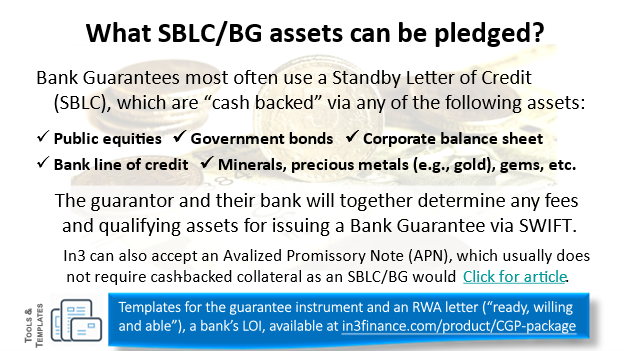

Asset options for the bank’s SbLC or Bank Guarantee issuance for their client’s project completion surety. Click to enlarge

Answer: Like Demand Guarantees used for trade finance (so-called Documentary Letters of Credit, which can also be called an SbLC under the same international banking rules), it is often assumed that the funds underlying the guarantee will be used at the completion of this transaction, to pay the seller. Here, for project finance, we are doing the opposite – not using the funds (transferring to the seller) but instead releasing the guarantee upon completion of the project, leaving the underlying collateral, if any, untouched. The fact that the asset value of the guarantee will not be touched (the family office would only consider “calling” or drawing on the guarantee as the last resort, in case of obvious fraud) means bankers can and often will accept non-cash assets as the underlying collateral for issuing the guarantee. If they assume it is a trade-related Documentary LC, or at all “exposed” to being called or drawn instead of its true purpose, they will expect cash or equivalent “liquid” asset classes such as a line of credit or something similar. When bankers properly grasp the phrase “as the last resort” (we will not and must not make such a claim, as that would put us in court with a black eye, all parties quite upset about how we missed the fraud despite all our best efforts) they can accept a variety of assets such as public equities, appraised artwork, developed real estate, a company’s balance sheet….

In3 uses a financial guarantee as project completion assurance, which means the guarantee must remain “operative” only until the project is built and commissioned. Either a Bank Guarantee / Standby Letter of Credit (BG/SbLC) or an endorsement (Aval) on a commercial Promissory Note (AvPN), usually under URDG ICC 758, would be released and any collateral unblocked upon its expiration date once the project reaches Commercial Operation Date (COD).

The Completion Assurance guarantee would not be used for any other purpose than assuring that the project reaches COD. It cannot be arbitrarily called or “drawn” or cashed. More on this here.

The perceived cash requirement may stem from the creditworthiness of the party requesting the guarantee. “Cash backed” does not necessarily mean cash, even for this “demand guarantee” in the form of a BG/SbLC, Advance Payment Guarantee or Blocked Funds instrument, so ask the banker(s) what they would accept as collateral only once they have understood this wider context. Their willingness to accept non-cash collateral varies widely, as do the fees they would charge for issuing the proper instrument (per our template) via SWIFT. Shop around?

But for an Avalized Promissory Note (article on AvPN), in order to obtain the bank’s Aval (their stamp of endorsement) on the 1-page Promissory Note per our template, the bank might be reluctant to provide this if the requestor is not adequately creditworthy in their eyes, as that could make the bank responsible in case the issuer defaults and does not have sufficient financial depth to honor their own promissory note obligation.

If the party requesting the Aval is not, in fact, reasonably creditworthy, the bank will either make unreasonable demands, such as suggesting that the bank would be effectively co-signers for the loan (not true for 3 different reasons — (a) there is no AvPN during the debt service after COD is reached, (b) the PN is company-issued, not the bank’s direct obligation, and (c) URDG ICC 758 makes it quite clear that the issuing party is at stake, not the endorser), or the bank will sometimes just refuse, saying “no, we can’t provide an Aval.” What they actually mean is that they don’t want to. A reasonably creditworthy party can push back and insist that the undertaking is safe, and necessary, to secure funding. The bankers, properly informed, will often come around.

But the lack of creditworthiness means other pathways must be pursued, with separate/additional collateral or higher fees, or both, than the AvPN approach.

But that said, many bankers initially believe a guarantee is not possible for different reasons, such as the perception that a “cash-backed, irrevocable, divisible, assignable and transferable” instrument could be called or used arbitrarily. That’s just not so. Read on ….

2) Myth #2: The guarantee itself represents a serious risk exposure to the bank and their customer – there is nothing that prevents it from being called or cashed from the start.

Not in this case. Consider these facts:

-

- We cannot arbitrarily call or draw on the instrument. The rules are well-established, where we have a preference for the Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees (URDG) ICC Pub No 758 (more on URDG, with independent legal review, well-proven since 2010). In fact, these same rules (or more commonly ISP98 or UCP) can also be used for Myth #1’s Documentary Letters of Credit, itself a point of widespread confusion. For a project’s completion guarantee under URDG 758, in particular, it is quite difficult to call or otherwise make a claim against the issued instrument, even in the event of breach of contract. First, there’s a strong counter-incentive to use the instrument to enforce the funder’s rights. We would have to prove malfeasance/fraud (clearly defined via our Loan Agreements) in the courts. That burden of proof is on us, making the bank’s involvement in the entire undertaking reasonably safe if the party asking for the guarantee is not fraudulent. If there is deliberate foul play, the more sensible solution is to fix (called “cure”) the problem(s) by proper notification seeking resolution in the manner proscribed in the loan agreement. We would rather make changes and accommodate whatever has gone wrong (sometimes the team discovers unforeseen problems with the site, one of the contractors, the suppliers, … or other circumstances that result in non-performance) than call the instrument. The guarantee is a backstop to ensure the funding is used in a responsible manner. It also assures the parties that cooperation is going to be better than giving up, walking away, or prolonged finger-pointing.

- The instrument is governed by the Loan Agreement between our family office and the project’s developer. That defines the commercial terms and conditions. Only upon uncured breach of contract can the instrument be called, and even then it is difficult to make a claim (we would end up having to prove there was malfeasance/fraud), thus the real purpose of this completion surety is to filter out such fraudulent actors. If the parties are not fraudulent, there is literally nothing to worry about. The intent is to ensure that the parties work together to resolve an issues that crop up so that the project gets finished and commissioned.

- The callable value of the instrument, in the event of breach of contract, is limited to the amount of family office funding transferred against it (or the instrument’s face value, at most) at any given point in time. This also limits the bank’s liability or “exposure,” as the parties will be able to monitor funding as it arrives from the family office into the Special Purpose Vehicle’s bank account. The Family Office’s bank pre-approves a monthly draw schedule, which makes each transfer automatic and guaranteed to occur. As the funding arrives and is deployed to procure and then construct the project assets, therein lies tangible value that cannot be lost.

- When first issued, the instrument has ZERO call value prior to the first transfer from our bank. In fact, it is not yet “irrevocable” and could be returned or “unwound” if there are conditions that are not to the bank’s liking – such as, if the project is cancelled, or if the family office does not deliver the agreed-upon funding. We cannot think of any reason why the bank would actually do that, but it is nonetheless their right prior to first drawdown of project funding. If other issues crop up, the parties will work together to resolve them. Simple.

- This structure (noting the facts above) protects all the parties and counterparties in the transaction. We won’t ask for any commitment whatsoever until after our Due Diligence and when we put a binding offer on the table, negotiate and enter all contracts, which gives the bankers and stakeholder plenty of time to review the resultant Loan Agreement (key because it governs the instrument’s use), prior to delivering the signed (Aval-endorsed) instrument hardcopy.

Conclusion: This project financing is far faster, more accessible (for up to 100% financing, include an equity investment), affordable, and certain than without a completion assurance guarantee. We use a pre-qualification step to make sure this advantageous funding is feasible, and so we won’t waste anyone’s time. We can provide quick yes/no answers to a complete pre-proposal – typically less than 48 hours. Financial closing is fast and reliable – we promise 30 days or less from inception to receipt of the hardcopy by the funding bank, assuming the client and the sending bank do their part. First funding arrives from the Family Office’s bank at most 30-45 days after closing with the remaining funds automatically scheduled until finished.

3) Myth #3: The client already has a contractor providing performance/completion bonds. Why can’t we just use that? Why do you need anything else?

Answer: We cannot use Insurance instead of a bank-involved instrument, also called a “financial guarantee.” Insurance is from an insurance company, not a bank. A guarantee used by the funder’s bank for Completion Assurance constitutes a Financial Guarantee because we are arranging a bank-to-bank transaction, in the form of equity and debt project finance, where the counterparty’s insurance is not a bank.

In the event of developer default, the contractor might make a claim and/or seek legal damages. In the event of contractor default, or other non-performance, that is why developers often request bonds or insurance to resolve such issues that on occasion arise between the developer and the contractor. But this has nothing to do with the financial guarantee required to secure the funding in the first place. For more, see Success Tip 5.2, “What about insurance as a completion assurance guarantee?”

4) Myth #4: The bank’s Ready, Willing and Able (RWA) letter is an irrevocable and binding commitment to deliver the financial guarantee.

Answer: Actually, no. Our RWA letter template, as written, is conditioned or contingent upon the existence of a funding commitment from our partners, and there are a lot of moving parts that could negate it, effectively making it null and void. It is issued on behalf of the bank’s client to demonstrate the intent and capability of the client to enter into the contemplated financial transaction (delivery of funding for one or more construction projects). The “ready” part is a bit of a misnomer. The RWA anticipates the time when the funding is under contract, which follows from our Due Diligence if all is in order. Then and only then would the bank be asked to do its part, so first the client must perform theirs. It should be a “Willing and Able” letter, not RWA, but this is the traditional name for this bank’s LOI. See technical steps for the sequence of events leading to financial closing. More on RWA letters

Summary & Conclusion

Many other misperceptions and/or myths are busted via this program’s FAQ – see CAP’s Frequently Asked Questions. If these points do not not address your banker’s particular concerns, please discover and clarify the precise question(s) or concern(s) they do have and ask us to assist with clarifying. This important communication is the real work.

For the complete technical protocol in summary form download this 1-page PDF.

Thank you for your interest in the In3’s CAP funding and here’s to our mutual success!